Ten years before anyone drunk or sober seriously discussed independence, Americans in the Thirteen Colonies faced a crisis that helped forge their national identity and began the agonizing process of questioning whether they were truly equal to their British brethren. During May 1765, the controversy of the Stamp Act Crisis washed across the colonies like no other event before in colonial political and economic life when news of the tax’s passage on March 22 first reached the shores of North America. Frequently overlooked today except by professional historians, the bitter opposition to the Stamp Act prompted what would eventually become hallmarks of the American Revolution: the cry of “no taxation without representation” (if there had been bumper stickers in the 18th century, this would have been the motto of the Revolution); the Sons and Daughters of Liberty (organized political opposition to British policies among all walks of colonial life); and the riots and aggressive protests of Bostonians against the Stamp Tax (a prelude to similar outbursts a decade later that would trigger Lexington and Concord). The statement that the Stamp Act Crisis lit the fuse that burned toward the powder keg marked “revolution” has merit.

Parliament passed the Stamp Act, a bill that would impose a tax on the American colonies through tax stamps placed on all legal documents, newspapers, commercial documents, and even playing cards. Without the stamps, documents would be invalid and paper products illegal. The logic behind the Stamp Act was impeccable; the politics, deplorable. The cost of the French and Indian Wars to the British taxpayer was £320,000 – roughly equivalent today to a price tag of $266 million. But far worse was the debt the crown incurred during the war, which was one of the most expensive in human history at the time. The British government went into the red to the tune of £130 million, or about $28 billion in today’s inflation-adjusted economy. That is an amount equal to about half of what the United States spent alone to purchase updated fighter planes in 2008, and a large drop in the bucket compared to that year’s Department of Defense budget of about $481 billion. But in 1765 that was more than the British taxpayer had ever spent on national defense, and even though there were tangible benefits to the average British subject in the Mother Country (for example, continued trade with America and a steady stream of commodities and products from the colonies) the fighting had protected Americans who were British subjects. Charles Townshend,

one of the wizards of the account books attempting to develop a comprehensive financial plan for the empire’s defense, asked “… Now will these Americans, children planted by our care, nourished up by our indulgence, till they are grown to a degree of strength and opulence, and protected by our arms, will they grudge to contribute their mite to relieve us from the heavy weight of that burden which we lie under?” Between 1763 and 1775, nearly 4 percent of the British national budget was spent on maintaining an army in North America. The general sense in Britain was the American colonists should pay for their own protection, both past and ongoing.

However, there was fierce opposition from the American colonists, a response that left many in Parliament dumbfounded. The politically tone-deaf response of the king’s ministers to this opposition helps explain why the Stamp Act Crisis has been called the match that lit the fuse of the American Revolution. A post-war depression had left Americans strapped for hard cash – in short, they did not have the money to pay the tax. Standing laws such as the Sugar Act and Parliament’s limits on how much pound sterling could circulate in the colonies compounded the money shortage. The use of paper in a literate, commercial society was almost universal, and a tax on such commonly used items was sure to spark protest from every level of colonial society. Playing cards were taxed, so sailors looking to relax in port (often a rowdy bunch to begin with) would pay more for a friendly game of cards. Lawyers, by definition the most contentious and argumentative people in the colonies, had a new reason to pick a fight with the government. Newspaper owners, the makers of opinion, had cause to editorialize bitterly against the Stamp Act. Colonial merchants, who were the lifeblood of the British economic system, had even more excuses to flout the Navigation Acts through smuggling in order to make up profit losses. There even was the suspicion that the king’s ministers and MPs really believed that the Americans simply had too many economic opportunities, civil liberties, universities, and freedom for a part of the realm that should remember its place and submit to its betters. However, the crux of the matter was simple: They had been taxed without their permission. Even colonial opponents of the Stamp Act acknowledge that Parliament had a right to tax the British people, but the colonists had been allowed for almost 100 years to raise taxes through their colonial assemblies, the source of local government in the king’s name. “No taxation without representation” became the outcry of people whose organized opposition challenged the authority of the most powerful nation in the world at the time.

One of the most impressive accomplishments that emerged from this colonial unity was the Stamp Act Congress. In October 1765, nine colonies sent representatives to the city of New York. The political energy and momentum that the 27 delegates represented is nearly unprecedented in colonial American history, eclipsed only by the first and second Continental Congress. Strongly motivated by legitimate fear that the Stamp Act threatened colonial self-rule, the Massachusetts House led the way by calling for a colony-wide meeting to discuss a unified response, which eventually included resolutions defining the colony’s right to raise their own taxes and a petition calling on Parliament to acknowledge that body could not govern the colonies because of the great distance between Great Britain and America. Even the colonies absent from the Stamp Act Congress held assembly members who chafed on restrictions to their participation. The only reason Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia failed to send delegates was the royal governors had refused to call the assemblies into session so they could hold a vote to appoint delegates. Faced with the same dilemma, the assemblies in Delaware and New Jersey ignored their governor’s boycott of the Stamp Act Congress, gathered a few members to meet informally, and voted representatives who were sent to the Congress. New Hampshire sent no delegates, but approved of the Congress’ actions after the fact. No wonder Ceasar Rodney, a future signer of the Declaration of Independence and delegate from Delaware, called the Stamp Act Congress “an Assembly of the greatest Ability I ever yet saw.”

Concurrent with this Congress, and rising more rapidly after the submission of petitions from the Stamp Act Congress failed to convince Parliament to rescind the Stamp Act taxes, was the mobilization of the forces of protest. Just as it had led the call for a political solution to the Stamp Act crisis, Massachusetts led the way in organized opposition. Boston was a seaport town loaded with unruly sailors, aggrieved lawyers, struggling merchants, pamphlet and newspaper publishers, and ordinary folk who all had the most

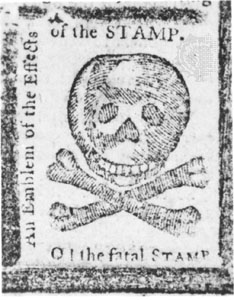

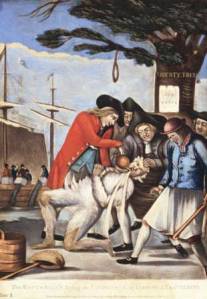

to lose through the imposition of the Stamp Act taxes on paper products, and many of these people were brewing a fight in the streets. Groups such as the Loyal Nine, a committee of men drawn from the ranks of the artisans and shopkeepers, began to plan public protests that would coincide with the first day that the act came into effect. This group soon expanded into the Sons of Liberty, a wildly successful protest movement that saw chapters spring up throughout the colonies, although the group is most associated with Boston. The Sons of Liberty raised political agitation to high art, sponsoring actions ranging from petitions calling for the end of the Stamp Act to boycotts of British goods to outright intimidation of British officials and their families. Their tactics included hanging the royal tax collector Andrew Oliver in effigy; destroying the Boston home of Thomas Hutchinson, the royal governor, by ransacking his residence and then burning it to the ground; and tarring and feathering royal tax collectors, a particularly gruesome form of public humiliation that scalded the naked body of the hapless victim from head to toe with hot tar, then rolled the man in bird feathers. Throughout the career of the Sons of Liberty the organization enjoyed the quiet blessing of the well-to-do and politically active that backed (or participated in) the Stamp Act Congress. In essence, the Sons of Liberty became the enforcement arm of the American cause against Parliament’s taxation of the colonists, exercising extralegal but very effective force on behalf of the aims and goals of the Stamp Act Congress.

Eventually, the protests and petitions had their effects. American boycotts alone drove many British merchants to despair, and they begged members of Parliament to rescind the tax so trade between Great Britain and America would resume. None other than William Pitt the Elder, one of the greatest statesmen in British history, condemned the Stamp Act, reminding his fellow M.P.s America’s true source of wealth to the British Empire was found in trade, not taxes. In 1766, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act with the king’s blessing.

But the Stamp Act Crisis was a prologue to how the colonies would approach the question of independence nearly ten years later. Many colonists kept alive the assertion of their rights that they had claimed during the years 1765-1766, defying the principle stated in the Declaratory Act that Parliament alone had the right to rule them in all cases. The Sons of Liberty remained a viable political organization in the colonies, celebrating the anniversary of the Stamp Act repeal until the beginning of the American Revolution.

In 1775, the men who once went to a congress called because of the Stamp Act crisis had learned their lesson. Much water in the political and historical sense had passed under the bridge by the time the Second Continental Congress met and then eventually considered and approved a Declaration of Independence. Furthermore, the unity Americans achieved during the Revolution and the years after was hardly unchallenged or undermined by the competing factions inside or outside of Congress. (In fact, the search for “a more perfect union” remains a hallmark of the American experiment to this day.) Finally, perhaps 20 percent of the population never supported the Revolution, remaining loyal to Great Britain. However, the supporters of the Revolution and independence knew that their enemies not only expected chaos and disunity when America declared independence – they planned on capitalizing on it as part of their war-fighting strategy. Once the Continental Congress accepted the idea of a Declaration of Independence, proponents of independence realized that only a unanimous vote of approval would be acceptable. If even one colony rejected the Declaration, it would indicate that the American cause lacked the support of an entire nation and that their hopes were fractured from the very beginning. Nothing less than survival hinged on that unity. As Benjamin Franklin reportedly quipped while signing the Declaration, “We must, indeed, all hang together, or assuredly we shall all hang separately.”

Pingback: O, The Fatal Stamp! | Delaware Online

Tar and feathering didn’t “scald” its victims. As far as I know, it didn’t kill or maim anyone, and being scalded would have probably been fatal back in the days before proper burn care.

The tar used was pine tar, not asphalt / road tar as we imagine today. It was often liquid at room temperature, at least in the summer.

Felix, thank you for reading the article. Actually, there are documented instances in colonial America of “tarring and feathering” causing great bodily harm to individuals including scalding. One low-level British customs officer applied to Parliament for a pension after he was tarred and feathered by Patriot vigilantes. He used chunks of his own shed skin as evidence of his suffering. In 1775, a Tory was dipped in hot tar and then his blistered skin was rubbed with dog dung. Whether it was asphalt or pine pitch, the melting points are very hot, hot enough to cause burns. Both were readily available in the seaport town of Boston because the substances were used to caulk ships. Some of our Founding Fathers and Mothers were part of a very rough crowd. I suggest you read this article from Smithsonian Magazine describing the tarring and feathering of John Malcom, a Boston Tory: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/The-Worst-Parade-to-Ever-Hit-the-Streets-of-Boston-200889461.html

The Smithsonian story only convinces me of the rarity of such burning hot tar. I have read too many stories involving tar and feathers to believe it would have been common if it had been commonly deadly; using feathers for humiliation would have been wasted on a corpse. The Smithsonian victim was a customs officer and loyalist who had previously been tarred and feathered for confiscating a ship, had a reputation for a temper, and had just threatened a kid on a snow sled and severely injured a man who came to the kid’s defense. He continually supported the king who the mob detested. All of this made the mob even less likely to go easy on him. It was winter with snow on the ground and a frozen harbor; the pine tar had to be heated, and I doubt they tried to heat it just barely enough.

And despite hours of being carted around Boston with burned skin and frozen tar, he survived and was able to give a deposition 5 days later. I still do not think scalding was very common. Scalding victims today have a hard time in modern hospitals; very few would have survived then.