There is one notable American whose deep belief in the principles of the Declaration of Independence is often overshadowed by today’s Presidents’ Day celebration. February 20 is the date of the death of Frederick Douglass (c. 1818-1895), a nineteenth-century orator, abolitionist, diplomat, and writer who was the most powerful for voice for equality between the races in Antebellum and Civil War America.

Born a slave, as a child he realized that literacy carried power and benefits in society. He asked the wife of one of his owners, Mrs. Sophia Auld, to teach him to read. When he learned the alphabet under her tutelage and could spell a few short words, his master forbade any further instruction. He continued on his own and taught himself to read using The Columbian Orator, a book of speeches and dialogues so popular that in remained in print throughout the 1800s. This book had a lasting impact on the young man. In it he read the speeches of William Pitt, George Washington, Cicero and others, and poems in the book which praised patriotism, courage, education, temperance, and freedom. Decades later, Douglass met Abraham Lincoln (who had also benefited from the book) and they both discussed the impression it had made on their intellectual development.

Douglass escaped slavery in 1838, travelling north until he eventually settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts to work in shipyards. However, his obvious intelligence and oratorical gifts led to him giving speeches for local abolition societies. He was such a fine speaker, and equally fine writer, that many considered him a fraud – evidence of the contemporary racist idea that blacks were the intellectual inferiors of whites. He went on to edit an abolitionist newspaper, which became one of the mostly widely read anti-slavery publications in the nation.

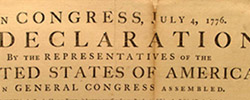

Of all men, Frederick Douglass had the least cause to believe in a nation that had deprived him of the natural right to liberty. Despite his background as an enslaved American who had lived under Southern concepts of liberty that justified human chattel, Douglass used the Declaration as the inspiration for perhaps the greatest anti-slavery speech given before the Civil War. Douglas delivered the speech “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” on July 5, 1852, before a packed audience at an anti-slavery meeting in Rochester, New York. Tempers were high and disgust with the United States widespread among the audience, which was mostly sympathetic whites aligned with William Lloyd Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society. Garrison had declared that both the Founders and the U.S. Constitution were racist, and had even recently argued that the North should secede from the South. Douglass rejected this view, declaring that the American Revolution and the ideas espoused in the Declaration were admirable, uniting the nation:

Fellow Citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were brave men. They were great men, too, great enough to give frame to a great age. It does not often happen to a nation to raise, at one time, such a number of truly great men. The point from which I am compelled to view them is not, certainly, the most favorable; and yet I cannot contemplate their great deeds with less than admiration. They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for the good they did, and the principles they contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory.

If the principles they contended for united all Americans (black and white, slave and free) then there was unfinished business that should be based on those American principles, including the self-evident truth that all men are created equal.

Would you have me argue that man is entitled to liberty? That he is the rightful owner of his own body? You have already declared it. Must I argue the wrongfulness of slavery? Is that a question for republicans? Is it to be settled by the rules of logic and argumentation, as a matter beset with great difficulty, involving a doubtful application of the principle of justice, hard to be understood? How should I look to-day in the presence of Americans, dividing and subdividing a discourse, to show that men have a natural right to freedom, speaking of it relatively and positively, negatively and affirmatively? To do so, would be to make myself ridiculous, and to offer an insult to your understanding. There is not a man beneath the canopy of heaven that does not know that slavery is wrong for him.

If logic would not work, shame did – the speech was a rousing success.

Douglass is one of this nation’s greatest citizens. His autobiography Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave is a testament of human freedom and deep faith in the hope of better things to come for him and his race. After the U.S. Civil War, he held numerous public offices including U.S. Marshal and counsel-general to the nation of Haiti. In 1888 during the Republican National Convention, he was also the first black American to receive a nominating convention vote as a presidential candidate from a major party. He remained a tireless opponent of racism and bigotry, whether toward blacks, American Indians, immigrants, or women. “I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong,” he once said. Frederick Douglass deserves more recognition from a nation that finally realized the promise “all men are created equal” is truly the national creed.

The First Black Lawmaker in the U.S. Senate

The first black American lawmakers elected during Reconstruction. Hiram Revels (R-Mississippi) is on the extreme left.

I will soothe my temper regarding Oscar’s snobbery last night toward the film Lincoln by noting one of the most important yet least-appreciated anniversaries in American political history. On this date in 1870, Hiram Rhodes Revels became the first black American elected to the U.S. Congress. An African Methodist Episcopal minister and organizer of two regiments of “colored troops” during the U.S. Civil War, Revels was elected by a strictly party line vote in the Mississippi Legislature as a Republican senator during Reconstruction. He was the U.S. senator from Mississippi from 1870-1871 — the exact same Senate seat once held by Jefferson Davis, the former president of the Confederacy. Revels served with great distinction and achieved national recognition for his efforts to economically improve his state through federal support of railroad construction. After his term in the Senate, he became the first president of Alcorn State University in Lorman, Mississippi. As in the case of most political strides made by black Americans during Reconstruction, the “redeemer” governments of Southern Democrats worked to prevent blacks from either voting or holding office through Jim Crow laws that lasted well into the 1960s. A black would not represent Mississippi in the U.S. Congress until 1987 when Mike Espy was elected to the House of Representatives by voters in his Congressional district.

Leave a comment

Filed under Commentary, History of the Declaration of Independence

Tagged as Black History Month, black lawmakers during Reconstruction, Hiram Revels, Jim Crow laws, Reconstruction, redeemers, U.S. Civil War