Smithsonian Magazine has published some examples of the work of John C. Guntzelman, who has colorized Civil War photos by Matthew Brady and Alexander Gardner in his book The Civil War in Color: A Photographic Reenactment of the War Between the States. I admit that I was a skeptic when I heard of the process. Colorization often reduces fine art like cinema or old photos to garish cartoons. Yet, the results are stunning. The article is well-worth reading for a taste of what the full book contains.

Smithsonian Magazine has published some examples of the work of John C. Guntzelman, who has colorized Civil War photos by Matthew Brady and Alexander Gardner in his book The Civil War in Color: A Photographic Reenactment of the War Between the States. I admit that I was a skeptic when I heard of the process. Colorization often reduces fine art like cinema or old photos to garish cartoons. Yet, the results are stunning. The article is well-worth reading for a taste of what the full book contains.

Tag Archives: U.S. Civil War

The Civil War, Now in Living Color

Filed under Commentary

Happy Birthday to the Bard of American Democracy

Walt Whitman, born this day in 1819 in West Hills, New York, presents a rare combination in American letters. The hang ups of literary critics pondering his sexual identity and the erotic character of Leaves of Grass are distractions. He broke the boundaries of poetry with his essay-like musings on the nation’s political character, the worth of free labor, and the necessity (as well as tragedy) of the U.S. Civil War. His journalistic writing is some of the best of his times on topics ranging from the founding of the Free Soil Party to the rise of baseball as the national sport. Old-fashioned as the term may be, I still favor the appellation “the bard of American democracy” as an apt description of Whitman’s ability to poetically “sing” about the founding values that shaped 19th century American political and economic practices for the good. In addition, no American poet ever captured an understanding of the character and significance of an American president like Walt Whitman did with Abraham Lincoln.

So, it is fitting today to let one small sample of Whitman’s poetry speak for him. The eerily beautiful “Vigil Strange” is among the most moving of his Civil War poems from Drum-Taps, which was published in 1865 before it was later incorporated into Leaves of Grass.

Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field One Night

Vigil strange I kept on the field one night;

When you my son and my comrade dropt at my side that day,

One look I but gave which your dear eyes return’d with a look I shall never forget,

One touch of your hand to mine O boy, reach’d up as you lay on the ground,

Then onward I sped in the battle, the even-contested battle,

Till late in the night reliev’d to the place at last again I made my way,

Found you in death so cold dear comrade, found your body son of responding kisses,

(never again on earth responding,)

Bared your face in the starlight, curious the scene, cool blew the moderate night-wind,

Long there and then in vigil I stood, dimly around me the battle-field spreading,

Vigil wondrous and vigil sweet there in the fragrant silent night,

But not a tear fell, not even a long-drawn sigh, long, long I gazed,

Then on the earth partially reclining sat by your side leaning my chin in my hands,

Passing sweet hours, immortal and mystic hours with you dearest comrade—not a tear,

not a word,

Vigil of silence, love and death, vigil for you my son and my soldier,

As onward silently stars aloft, eastward new ones upward stole,

Vigil final for you brave boy, (I could not save you, swift was your death,

I faithfully loved you and cared for you living, I think we shall surely meet again,)

Till at latest lingering of the night, indeed just as the dawn appear’d,

My comrade I wrapt in his blanket, envelop’d well his form,

Folded the blanket well, tucking it carefully over head and carefully under feet,

And there and then and bathed by the rising sun, my son in his grave, in his rude-dug

grave I deposited,

Ending my vigil strange with that, vigil of night and battle-field dim,

Vigil for boy of responding kisses, (never again on earth responding,)

Vigil for comrade swiftly slain, vigil I never forget, how as day brighten’d,

I rose from the chill ground and folded my soldier well in his blanket,

And buried him where he fell.

(1865)

Filed under Commentary

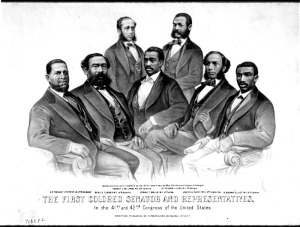

The First Black Lawmaker in the U.S. Senate

The first black American lawmakers elected during Reconstruction. Hiram Revels (R-Mississippi) is on the extreme left.

I will soothe my temper regarding Oscar’s snobbery last night toward the film Lincoln by noting one of the most important yet least-appreciated anniversaries in American political history. On this date in 1870, Hiram Rhodes Revels became the first black American elected to the U.S. Congress. An African Methodist Episcopal minister and organizer of two regiments of “colored troops” during the U.S. Civil War, Revels was elected by a strictly party line vote in the Mississippi Legislature as a Republican senator during Reconstruction. He was the U.S. senator from Mississippi from 1870-1871 — the exact same Senate seat once held by Jefferson Davis, the former president of the Confederacy. Revels served with great distinction and achieved national recognition for his efforts to economically improve his state through federal support of railroad construction. After his term in the Senate, he became the first president of Alcorn State University in Lorman, Mississippi. As in the case of most political strides made by black Americans during Reconstruction, the “redeemer” governments of Southern Democrats worked to prevent blacks from either voting or holding office through Jim Crow laws that lasted well into the 1960s. A black would not represent Mississippi in the U.S. Congress until 1987 when Mike Espy was elected to the House of Representatives by voters in his Congressional district.

Spielberg Says His Biopic “Lincoln” Is No Political Football

An interesting story from Yahoo about Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln: In an interview, the director is adamant that the historically based film has  no current political agenda. According to the article, he asked distributors to release the film after the November elections to avoid controversy. “Don’t let this political football play back and forth,” the story story quotes him as saying in the interview.

no current political agenda. According to the article, he asked distributors to release the film after the November elections to avoid controversy. “Don’t let this political football play back and forth,” the story story quotes him as saying in the interview.

The real story in my opinion is the tantalizing sneak peak offered the media during the showing. Viewers not only praised Daniel Day-Lewis’s performance but also Tommy Lee Jones’s portrayal of Thaddeus Stevens, which critics say should receive a nod from Oscar. Most importantly, the history seems sound in the film. I continue to hope for the best when the film finally opens nationwide in mid-November. Lincoln should live up to the expectations of viewers like me.

What John Quincy Adams Tells Us About One-Term Presidents

Courtesy of The Wall Street Journal, prolific biographer and writer Harlow Giles Unger offers an essay on John Quincy Adams, a forgotten Founding Father whose career before and after his single presidential term is little remembered even by many professional historians. As Unger writes, JQA was “the oldest son of John and Abigail Adams, John Quincy Adams seemed destined for greatness from birth. He served under Washington and with Lincoln; he lived with Ben Franklin, lunched with Lafayette, Jefferson, and Wellington; he walked with Russia’s czar and talked with Britain’s king; he dined with Dickens, taught at Harvard … negotiated the peace that ended the War of 1812, freed the African prisoners on the slave ship Amistad … restored free speech in Congress, (and) led the anti-slavery movement … .” It was a stellar career, one that Unger portrays excellently in his new biography of the polymathic president.

One other message of the article is that JQA could serve as a role model for President Obama should he lose this November and himself enter the ranks of one-term presidents. (“One-term president” is usually a criterion used to suggest that the individual was also a failed president.) I suggest the best purpose of the essay is to remind readers of the long-lasting living link between the founding period and the mid-nineteenth century. People like John Quincy Adams (d. 1848), Dolley Madison (d. 1849), James Monroe (d. 1831), and even the infamous Aaron Burr (d. 1836) were long-lived individuals who spoke frequently of the times which created the United States. These individuals witnessed the formative years of American history from the dawn of the American Revolution to the eve of the Civil War. New research on the War of Revolution, how the Declaration of Independence was received by Americans of the era, and the political attitudes of the Founding Fathers and Mothers would be greatly expanded by new examination of the papers of these individuals, as well as memoirs and commentators written by family and friends that recall the reminiscences of those seminal individuals.

What the American Revolution began, the Civil War completed: Allen Guelzo on the Emancipation Proclamation

Paul Huard (left) and Allen Guelzo (right). I regret the stupid grin on my face, but Dr. Guelzo had just cracked a typically clever joke.

In 2010, I was fortunate to study for a week under the direction of Allen Guelzo, professor of history and director of the Civil War Era Studies Program at Gettysburg College. The summer institute was the result of the generosity of the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, an organization I have only half-jokingly described as treating historians and teachers of U.S. history like rock stars. The seminar on Abraham Lincoln was easily one of the best scholarly experiences I had in recent years and it was a pleasure to finally meet the man whose works (such as Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America) are among the most insightful tomes on Mr. Lincoln and the U.S. Civil War. Recently, the Wall Street Journal published an article by Dr. Guelzo about the 150th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. Now that the piece is no longer subscriber-only content, I can share the essay. Though brief, it captures what Lincoln thought was at the heart of the U.S. Civil War. “The American republic was an ‘experiment’ to see if ordinary people, living as equals before the laws and without any aristocratic grades or ranks in society, really were capable of governing themselves,” Guelzo writes. Emancipation, he says, was Lincoln’s “central act” of the presidents administration and “certainly there has been no presidential document before or since with quite its impact.” I consider that assessment a concise expression of a reason why Lincoln is often considered the man whose Romantic sense of nationalism and liberty finally added the “complete” understanding to the Declaration of Independence that was already there for all to see. But it took the deadliest war in American history to complete what Jefferson and the Patriot cause began.

Let Freedom Ring: 150 Years Since The Emancipation Proclamation

On this day a century and a half ago, Abraham Lincoln issued the first version of the Emancipation Proclamation, one of this nation’s most important political documents and the beginning of the official transformation of the Union’s wartime strategy to the goal of freeing enslaved Americans. His proclamation warned the Confederate states that if they remained in rebellion against the U.S. on Jan. 1, 1863, Lincoln as commander-in-chief would on that day declare all slaves to be free in areas under Confederate control. Lincoln’s measure came just five days after the agonizingly costly Northern victory at Antietam, easily the bloodiest single day in American military history.

The decision to issue the proclamation may have been one of the most politically dangerous wagers ever made by an American president. An essay in yesterday’s New York Times by Richard Striner, a history professor at Washington College, points out that Lincoln received warning from fellow Republicans that he had just lost the upcoming elections for the Republican Party. Postmaster General Montgomery Blair warned that it would “endanger our power in Congress, and put the next House of Representatives in the hands of those opposed to the war, or to our mode of carrying it on.” Southerners would be outraged by the decision, seeing it as confirmation of every fear that had driven them to secession and war.

We often forget that Lincoln was an unpopular president, a plurality president elected with about 40 percent of the popular vote in an election with three other candidates, and a president during a controversial war killing more Americans than all of the nation’s other wars combined up to that time. With that in mind, I have often considered the Emancipation Proclamation, written as it is in the dull prose of a lawyer, the greatest and most principled statement of moral leadership by any president. Lincoln lived by the words of the Declaration of Independence and those words are ringing enough for all times. It was through that presidential proclamation, its twin issued in 1863, and the gutsy decision to fight a great war to purposeful victory that made the words of both documents matter for all Americans. Liberty is measured by results, not by the number of rhetorical flourishes in an executive order or the flowery prose displayed on a TelePrompter.

Full Trailer for Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln” available on YouTube

I always try to remember that a trailer often packages a movie’s best two minutes when it comes to what you see in the theater while nibbling  your popcorn and waiting for the main attraction. Still, I am impressed by what Steven Spielberg promises moviegoers in the full trailer released Thursday for his Lincoln, which opens November 9. Daniel Day-Lewis displays a characterization of Lincoln as a brooding, intense, and highly principled man who struggles with his role in history. Even more promising are the supporting actors. Tommy Lee Jones portrays Radical Republican firebrand Rep. Thaddeus Stevens, one of the most powerful lawmakers during Lincoln’s administration and an often sarcastic gadfly who endlessly goaded President Lincoln to do battle against the Slave Power and issue an emancipation proclamation. Spielberg cast David Strathairn as William Seward, the 16th president’s secretary of state and a founding force in the young Republican Party who vied for the party’s nomination during the Election of 1860. Despite the schmaltzy tones of sentimentality that comes from the piano tinkling away in the soundtrack, the intensity of the national division during the Civil War comes through loud and clear in the scenes selected for the trailer. Most importantly, there are hints that Lincoln’s devotion to liberty and freedom that he repeatedly acknowledged as stemming from his dedication to the principles of the Declaration of Independence will take center stage in the film. Movies rarely do a good job of presenting history rather than just simple entertainment, but I have even more reason to believe Spielberg’s film will the double-A plus biopic I hope it will be.

your popcorn and waiting for the main attraction. Still, I am impressed by what Steven Spielberg promises moviegoers in the full trailer released Thursday for his Lincoln, which opens November 9. Daniel Day-Lewis displays a characterization of Lincoln as a brooding, intense, and highly principled man who struggles with his role in history. Even more promising are the supporting actors. Tommy Lee Jones portrays Radical Republican firebrand Rep. Thaddeus Stevens, one of the most powerful lawmakers during Lincoln’s administration and an often sarcastic gadfly who endlessly goaded President Lincoln to do battle against the Slave Power and issue an emancipation proclamation. Spielberg cast David Strathairn as William Seward, the 16th president’s secretary of state and a founding force in the young Republican Party who vied for the party’s nomination during the Election of 1860. Despite the schmaltzy tones of sentimentality that comes from the piano tinkling away in the soundtrack, the intensity of the national division during the Civil War comes through loud and clear in the scenes selected for the trailer. Most importantly, there are hints that Lincoln’s devotion to liberty and freedom that he repeatedly acknowledged as stemming from his dedication to the principles of the Declaration of Independence will take center stage in the film. Movies rarely do a good job of presenting history rather than just simple entertainment, but I have even more reason to believe Spielberg’s film will the double-A plus biopic I hope it will be.

Filed under Commentary

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and the U.S. Civil War

A battlefield memorial at Gettysburg National Military Park. Photo by Paul Huard

The issue of mental illness arising from the trauma of combat is nothing new. Homer described the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the Illiad. When Achilles’ close friend Patroclus dies in combat, Achilles cries out, “My comrade is dead, / Lying in my hut mangled with bronze, / His feet turned toward the door, and around him, / Our friends grieve. Nothing matters to me now” and then embarks on a killing spree that is more like an attempt at suicide than warfare. Call it what you will: “shell shock,” combat fatigue, survivor’s guilt. PTSD is as old as history.

The U.S. Civil War was no different. While researching another topic, I stumbled across an article from The New York Times by University of Georgia graduate student Dillon Carroll on PTSD and the Civil War.

A key quote:

Despite all the valor shown during the Civil War, despite all the worthiness of the cause, soldiers both North and South were often damaged men long after the war was finished. I see a need for historians to take a close look at what might be an untouched area of study regarding the real toll of America’s worst war. What they find will not only expand our understanding of that period of history but hopefully reinforce the current argument that the United States needs to provide better services and better outreach to a generation of combat veterans who have fought in America’s wars since 9-11.

2 Comments

Filed under Commentary, Military History, Scholarship and Historians

Tagged as Civil War, military history, post-traumatic stress disorder, PTSD, U.S. Civil War