With just a few weeks before the First Tuesday in November, the presidential race is tighter than a mosquito’s butt in a nosedive. Face it: Nothing is moving the needle. Most of the major polls have the race between President Barack Obama and Gov. Mitt Romney in a dead heat in spite of millions of dollars spent in television ads, the bully pulpit of the president’s incumbency, Joe Biden’s dental work, and debates where the candidates either seek “gotcha moments” or act like they just want the whole weary mess to conclude. Will anything shed light on who is the best choice for the highest office in the land?

Let me suggest a novel solution. If Obama and Romney simply take the epic of the zombie apocalypse seriously and spend time answering questions about the cleverly hidden messages regarding political theory and policy realities in zombie lore, Americans will be better able to make a clear and confident choice. If you think that sounds silly keep in mind that AMC’s The Walking Dead, cable television’s most watched series ever, debuted its third season Sunday and 10.9 million fans could not get enough of the lurking undead. (And I am not talking about how the Dearly Departed vote in Chicago elections.) In comparison, Congress, the greatest deliberative body on the planet, currently has about a 13-point approval rating in the RealClearPolitics average of reliable polls. According to the same index, both President Obama and Gov. Romney languish below 50 percent approval. One thing that could liven up the chances of determining a victor would be getting this race linked to the dead – that’s where Americans’ interests lay. (By the way, time for a quick joke. Q: Why did the zombie apocalypse bypass the presidential debates? A: Because neither candidate had any brains.)

Before you excoriate me for offering a corny parallel between pop culture and popular politics, open your mind for just a moment. As readers of my blog know, I spend a lot of time exploring American political history and thought, particularly the message and influence of the Declaration of Independence and the Founding Period. One of the basic ideas in the Declaration is the social contract, an agreement between rulers and the ruled to honor the consent of the people in exchange for peace, security, and freedom. Thomas Jefferson summed up the idea concisely, indicating how the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness are protected, not granted, by government:

That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.

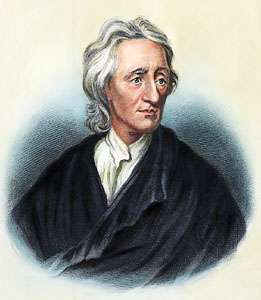

Two of history’s greatest political philosophers, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, are widely credited with legitimizing this theory of government. Hobbes argues that the legitimate state is based on the ruled giving up their freedoms in exchange for the security and protection granted the people by an absolute monarchy. He famously saw life as a state of “continual fear and danger of violent death, and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” If you removed government by a mighty and powerful sovereign, you returned to a state of nature where there is the bellum omnium contra omnes – “the war of all against all,” a state of vicious, devouring destruction. John Locke, too, believed in the state of nature, but his social contract has people developing a civil society to resolve conflicts while they maintain the right to protect their life, liberty, and property to hold violence at bay. He also believed human nature had the qualities of tolerance and reasonability, two tendencies that take a sunnier view regarding whether there is any hope for humankind. Think of them respectively as the “daddy party” and “mommy party” of political ideologies in the Age of Enlightenment.

So what does an understanding of the philosophical underpinnings of Western democracy and a zombie outbreak have to do with presidential politics? I don’t claim to have any inside baseball regarding the intellectual leanings of the writers and producers of The Walking Dead, but that show sure includes an enormous amount of political philosophy. As far as I am concerned, it’s a simple formula: The nation’s love affair with zombies plus acknowledgement of the social contract plus probing Z-Day-themed questions from the media during the last weeks of the campaign equals America’s moment of clarity. Want a metaphor for our current political and economic world (and I don’t mean the silly term “zombie banks”) now fraught with collapses of all types? Zombies in the show are corpses slaughtered by a virus that burns out the victim, re-animates the corpse hours later, and strips the undead of any brain functions except vicious behavior and a taste for human flesh. If that isn’t a Hobbesian metaphor for every kind of self-destructive political chaos in the world ranging from the rise of radical Islam and its nihilism to chilling of the Arab Spring into an extremist Arab Winter, what is? That kind of comparison could prompt an adept reporter to ask, “Mr. President, based on your current foreign policy of continuing to advocate foreign aid to the government of Egypt although it is dominated by the Muslim Brotherhood, what will be your response to the catastrophic rise of the undead when they eat the population of Pittsburg?” (Probably sobs from the chief executive as he considers all the Democratic votes there.)

Furthermore, the band of survivors on the show is led by the character Rick Grimes, a sheriff’s deputy and family man who constantly struggles to hold his family together while fighting factions in the group who can’t decide their next move in this new and hostile world of ravenous zombies. Should that little group of humans decide to accept the absolute rule of the “Rick-tatorship” or strive for government that derives its just powers from the consent of the unbitten? Sounds like a Lockean dilemma to me, one that a president could answer when it comes to similar dilemmas regarding implementation or rejection of the Affordable Health Care Act, traditional marriage vs. gay rights, free market vs. government interventionist approaches to spurring our limping economy, and other conflicts begging for resolution. An on-the-ball reporter could ask, “Gov. Romney, you are now the standard bearer for a party that still espouses traditional values in a rapidly changing world. Considering that, what is your stance regarding zombie/the living marriage and how will justify your position to your party and the American people?” Ask questions like these, and you will hear some real answers.

Both men embrace big government solutions, although in some ways it’s a matter of degree. President Obama poured billions into Chevy Volts that turned out to be spendy lemons and dubious “shovel ready” projects that did nothing to prompt a recovery, while Gov. Romney helped transform Massachusetts into the land of RomneyCare, $50 abortions, judicially mandated gay marriage, and wall-to-wall gun control. One other cool thing about the zombie mythos is it is a subtle affirmation of classical liberalism, the political and economic theory espoused in the Declaration. Simply put, classical liberals believe deeply “the bigger the government, the smaller the citizen.” Government unchecked or over-encouraged has the tendency of growing larger, more oafish, and hungrier. Remember an oft-forgotten line from the bill of particulars in the Declaration listing acts of George III’s tyranny: “He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance.” Only individual liberty and the widest amount of freedom within the boundaries of law and morality can save humanity. Hey, in most zombie movies, who starts the plague? The government, that’s who! Some military chem-bio warfare project goes horribly, horribly wrong, there is a cover up, and the next thing you know there are thousands of sprinting cadavers and you are the blue plate special. On The Walking Dead, the only surviving doctor at the Centers for Disease Control is a nutball research scientist who locks all the doors and blows the place up with a fuel-air explosion so it will put everyone out of their misery whether they want it or not. (Was Sarah Palin right? Is that a kind of “death panel”?) FEMA, sharp as ever, is full of rapidly moving undead personnel, turning each refugee station into a Club Zed where it is not a place to get a meal – you are the meal. Ask both candidates how a bloated, inept federal government could cause the next zombie outbreak and you will get America’s attention. By the way, that also would be good time for both candidates to mention how they will work to loosen federal gun control laws so putting down the undead will be that much easier.

Laugh if you want. I say that The Walking Dead, World War Z, George Romero, and their undead counterparts in film and fiction have done more to teach people about Hobbesian and Lockean social contracts, the value of small government, and skepticism about politicians’ promises than all the political science courses and spilled ink of the chattering class combined. It’s time for the dead to rise and the candidates to put some life into this race. Zombies can help give America a hand as voters struggle to decide who should go to the White House. Or the whole arm. Or any other body part, for that matter.

Note: this post was updated Tuesday, October 16, to reflect viewership statistics for The Walking Dead.

“O, Say Can You Z” Gets Another Lease On Life

“O, Say Can You Z” Gets A New Lease On Life

Enforcing the Rick-tatorship in the Hobbesian world of the zombie apocalypse

My new friends at the on-line humor magazine ThirdRailers.com were kind enough to publish my “O, Say Can You Z” article published here in an earlier post. Here’s my take on why presidential politics and the zombie apocalypse are made for each other, and what the social contract described in “The Declaration of Independence” tells us about the brutal world of the undead. The article is updated for national publication. Click on the link above to read the article. UPDATE: I should note that the latest Gallup poll does have Mitt Romney at 52 percent, Barack Obama at 45 percent as the choice of adults surveyed. My article originally suggested that the polls remained tightly locked. However, the presidential race obviously remains close.

1 Comment

Filed under Commentary, History of the Declaration of Independence

Tagged as 2012 Election, Barack Obama, Declaration of Independence, John Locke, Mitt Romney, social contract, The Walking Dead, ThirdRailers.com, Thomas Hobbes